I have no desire whatsoever to be an environmentalist. None.

Studying nature and the environment? Yes, definitely.

Fighting one’s own government to try to get them to stop poisoning you and trashing the place you live? Nope.

There are many other pastimes I would rather pursue. The Japanese art of arranging natural stones – Suiseki? Sounds very cool.

Trying to convince a table of technocrats laden with heaps of conflicts of interest that if you kill fewer fish there will, in fact, be more fish alive? Ugh.

(Yes, that really happened to me at a major national forum on forests and rivers).

How do we solve the environmental problems facing us? We don’t. Not with the approach that they are “environmental.” That is, that they are in a separate category to be solved by “environmentalists.” That has not worked often enough and will not work fast enough.

Environmental problems are social, technical, political – even spiritual. They are gender problems and economic problems and equity problems and more. This is why they are so challenging.

This is also why they are fascinating. We are challenged to use our creativity and talents across disciplines and decades. The complex interdisciplinary nature of environmental issues and the imperatives for solutions are why they are such fertile ground for educators and for a revolution in education.

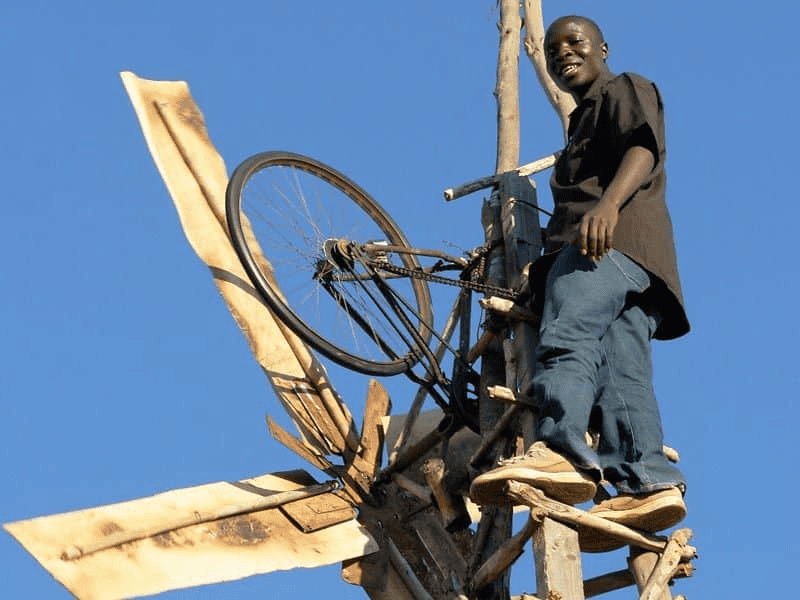

“The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind.”

William Kamkwamba was a boy in Wimbe, Malawi in the 1990’s. Poverty and drought were twin challenges for William and the people of Wimbe.

William was innately curious about all things electronic and mechanical and his curiosity and talents were aligned. When William’s family could not pay his school fees he would sneak onto the school campus and listen at windows or study alone in the library.

One day William discovered a book, “Using Energy,” and William’s life, and the world, were changed forever. William combined his talents for electronics, scrounging in the dump, and the knowledge he got from that book to build windmills that provided electricity and water to Wimbe for the first time.

His creativity and brilliance took him all the way to Dartmouth College and to the big screen as the inspiration for the film, “The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind.”

As a boy I watched huge swathes of forests in the mountains of Northern California hacked down. The rivers died. The plants and wildlife died. Eventually whole communities died. The forests that grew back over the following decades were fragments of what had been.

To this day they burn in ways that should never be. My Dad, a building contractor who made much of his living through using lumber, was endlessly pissed off.

The United States Forest Service was giving these forests away to lumber companies and ghost riding the future into brick walls. I spent years battling the Forest Service and private timber companies and that period nurtured and informed much of the interest in environmental problem solving, ecosystemology, and applied ecology I carry today. It also pointed to my direction in education.

Creative Forestry and the Songs of Birds

Scientists at Cornell University record bird calls and process the recordings to improve the management of forests over millions of acres of the Sierra Nevada mountains in California. They position hundreds of microphones across the landscape and by using the recordings to identify the numbers of ten species of birds in those forests they can learn a great deal about the health and structure of the forest.

By knowing how different birds relate to different forest conditions they can make good inferences about what’s going on out in the woods without having to do it the ways I learned; ways which all involved a lot of hiking with backpacks full of equipment (it also involved heat, wasps, and poison oak).

Our work produced so-so data that took so long to collect, crunch and interpret that it was often not useful by the time we were done. We simply couldn’t cover millions of acres and generate meaningful data.

Technology now offers possibilities for environmental science we could only dream of back then. Automatic recording units and machine learning allows for making sense of mountains of data in moments.

This is really cool stuff with great possibilities for protecting forests and wildlife. The potential for dynamic learning opportunities in schools within this realm is limitless.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s K. Lisa Yang Center for Conservation Bioacoustics is doing this. (P.S. I didn’t even know that “Conservation Bioacoustics,” was a thing).

Creativity in education can lead people to acts of heroism and global fame like William Kamkwamba, or to smaller ones like my Dad refusing to be derailed until he spoke directly (and in a masterfully terse manner that still makes me smile) to the head of the US Forest Service to get a destructive timber sale shut down.

Environmental issues are usually staggeringly complex – and interdisciplinary in the extreme. This makes them tough to deal with but also compelling intellectual challenges with room for a vast range of intelligences and talents to work together.

The Creative Revolution that Sir Ken Robinson challenged us to create is nowhere more important than in the noble paths to saving our Mother Earth.

Thanks for your attention.

Steven Greenleaf (Leafy)

07 May 2025 Steven Greenleaf